Making Trailmix #2: Is sugar addictive?

Sugar activates the same reward pathways in the brain as drugs; called the mesolimbic pathway & is ‘switched on’ by dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to motivation & reward. But is sugar addictive?

I love digestive biscuits. This might be very basic bitch of me, considering the fine array of biscuits at our disposal. But there’s just something about them dipped in tea that trumps everything else—pure heaven.

I’ve recently developed a habit in the van of enjoying 2-3 digestives after lunch with a cuppa. Of course, this isn’t inherently a problem as 80-90% of my diet is based on whole foods rich in protein, fibre, fat, and complex carbohydrates. So, a few biscuits with my tea probably isn’t doing me any harm.

But it’s not so much the biscuits I’m concerned about; it’s the habit. It’s become somewhat involuntary, and it’s no longer ‘a nice treat’ but something I do to avoid the discomfort of sitting with a craving and not acting on it.

So, what’s driving this? Is it the sugar? Well, I’m not mainlining bags of sugar—the vehicle of delivery (aka the biscuit) remains a crucial aspect of the craving, but if there was no sugar in the biscuit, would I crave it at all? Unlikely.

Addiction researchers use the term ‘addictive liability’ to define the addictive potential of a drug. Connected to a drug’s liability is its ability to raise dopamine levels above baseline, igniting reward pathways in the brain.

Research in rats (unfortunately, human evidence remains limited) has shown that intermittent sucrose (sugar) consumption can raise dopamine levels by up to 130% above baseline. Compare this to amphetamines, which have been shown to raise dopamine by 200-400% above baseline.

While it’s unclear exactly how much dopamine rises after sugar consumption, human research using questionnaires that “assess subjective dopaminergic and opioidergic effects of psychoactive drugs” suggests a strong link between sugar and the same rewarding pathways linked to addiction.

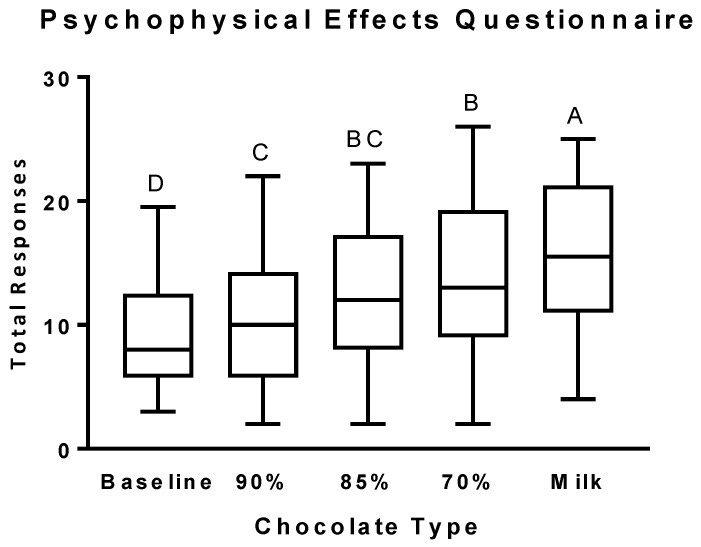

One study found a dose-dependent relationship between the sugar content of chocolate and the participant’s subjective effects on their reward pathways.

So, sugar’s addictive liability may be lower than common substances of abuse, as defined by its ability to increase dopamine. Still, the interaction is there, and its ubiquity in our environment means our brains can associate sugar with every aspect of our lives.

Wake up, feel tired, and have a coffee with sugar. Then, feel hungry and enjoy a bowl of cereal laced with sugar. Mid-morning, feel tired and hungry, and enjoy another coffee with sugar and a snack with - you guessed it - more sugar.

Whether hungry, tired, stressed, lonely, or bored, we can use it to soothe our discomfort. This then becomes our go-to coping mechanism, and every time we feel that discomfort rising, dopamine will increase in anticipation of sugar ingestion.

Dopamine isn’t a pleasure hormone per se; its role is to motivate. Each time we enjoy a piece of chocolate in front of the TV to keep our hands busy or feel low, we’re conditioning our brain - through dopamine release - to crave sugar. Repeating these behaviours reinforces this association over time.

There’s an argument that this is a form of addiction, as many people living with addiction will be using drugs to soothe the discomfort of an underlying trauma.

However, going cold turkey on heroin can lead to death due to the magnitude of the physical dependency. Sugar’s not in the same ballpark. If you stop eating sugar, you might experience some mild withdrawal symptoms for a day or two, but nothing life-threatening.

So, while sugar acts on the same reward pathways as drugs like cocaine and alcohol, for most of us, it’s probably more an issue of habit and association.

Suppose we learnt to soothe our discomfort in more helpful ways. In that case, we might see our brain’s reward circuitry shift away from sugar and toward exercise, meditation, sex (which increases dopamine by around 100X above baseline), reading, music, or social interaction.

For me, it was about changing my environment and removing the cue. Digestives are no longer on my shopping list. Out of sight, out of my digestive-induced dopamine-spiking mind.